Behavioral economics is all about understanding the strange ways we make decisions. It’s the study of why we don’t always act logically when it comes to decision making.

In today’s fast-paced world, understanding human behavior is crucial to success in business. While traditional economics assumes we always make smart choices, behavioral economics shows we often don’t. It looks at how emotions, biases, and social influences shape our decisions. Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman helped popularize this field.

In this guide, you’ll explore how behavioral economics can be used practically in marketing, product development, sales, and pricing. I’ll cover its fundamental principles and real-world examples to help you use human psychology to your advantage.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What is Behavioral Economics

- Behavioral Economics Principles

- Examples of Behavioral Economics

- Behavioral Economics Applications

- Best Behavioral Economics Books

- Final Thoughts

What Is Behavioral Economics?

Behavioral Economics Definition

Behavioral economics, a captivating and multidisciplinary field, serves as a bridge between psychology and economics, uncovering the intricate web of human decision-making processes. It acknowledges a fundamental truth: people don’t always act in a manner deemed “rational” by traditional economic standards, even when they possess the necessary information and tools for making optimal choices.

What Is the Difference Between Behavioral Economics and Classical Economics Models?

Classical economics and behavioral economics models diverge in their understanding of human decision-making. Behavioral economics delves into the reasons behind individual choices, such as why people delay investing in their 401(k)s or neglect adopting healthier habits despite knowing their benefits. It unveils that humans are not purely rational beings; they’re influenced by emotions, impulsivity, and their environment. In contrast, classical economic models typically portray individuals as rational actors consistently pursuing long-term goals or occasionally prone to random errors that average out over time.

What Is The Importance of Behavioral Economics?

Behavioral economics holds significant importance as it provides valuable insights into human decision-making. These insights have driven governments and businesses to develop policies and frameworks that promote more favorable choices. It underscores the essential nature of comprehending the human psyche in shaping effective economic strategies, pricing models, marketing campaigns, and products. By acknowledging the inherent complexities of human behavior, we can refine our approaches to better align with the genuine needs and preferences of individuals, ultimately leading to more successful and customer-centric strategies.

Behavioral Economics Principles

In the world of behavioral economics, the human mind is a fascinating realm where intricate biases and psychological quirks influence our decisions and actions. These behavioral economics principles shed light on the way we make choices, often revealing that our rationality is not as straightforward as we might think.

Affect Heuristic

A mental shortcut in behavioral economics that allows people to make quick decisions by incorporating their emotional responses. They base their choices on their gut feelings. Researchers have discovered that when people have a positive feeling about something, they tend to perceive the benefits as high and the risks as low, and vice versa. Therefore, the affect heuristic acts as a rapid, initial response mechanism in decision-making.

For example, if someone has wronged you, you may quickly conclude that this person is cold and unfriendly. Surprisingly, even if the person didn’t harm you intentionally, you may still harbor the same feelings towards them.

Anchoring

Anchoring is a behavioral economics bias that characterizes the human inclination to place excessive reliance on the first piece of information presented (referred to as the ‘anchor’) when making decisions.

For instance, when negotiating the price of a used car, the initial price offered often establishes a mental reference point that significantly influences the rest of the negotiation.

Availability Heuristic

A mental shortcut that relies on immediate examples that come to a given person’s mind when evaluating a specific topic, concept, method, or decision. People tend to heavily weigh their judgments toward more recent information, making new opinions biased toward the latest news.

For example, which job is more dangerous – being a police officer or a logger? While high-profile police shootings might lead you to think that cops have a more dangerous job, statistics actually show that loggers are more likely to die on the job than cops. This illustrates that the availability heuristic helps people make fast, but sometimes incorrect assessments.

Bounded Rationality

The idea that in decision-making, people are limited by the information they have, the cognitive limitations of their minds, and the finite time. As a result, they seek a ‘good enough’ decision and tend to make a satisficing (rather than maximizing or optimizing) choice.

For example, during shopping when people buy something that they find acceptable, although that may not necessarily be their optimal choice.

Certainty Effect

When people overweight outcomes that are considered certain relative to outcomes that are merely possible. This behavioral economics certainty effect makes people prefer 100% as a reference point relative to other percentages, even though 100% may be an illusion of certainty. Lower percentages or probabilities can be more beneficial in the long run.

For example, people prefer a 100% discount on a cup of coffee every 10 days to another more frequent but lower discount offer, even though the second option may save them more money in the long run.

Choice Overload

A cognitive process in behavioral economics in which people have a difficult time making a decision when faced with many options. Too many choices might cause people to delay making decisions or avoid making them altogether.

For example, a famous study found that consumers were 10 times more likely to purchase jams when the number of jams available was reduced from 24 to 6.

Less choice, more sales. More choice, fewer sales.

Cognitive Dissonance

A mental discomfort that occurs when people’s beliefs do not match up with their behaviors.

For example, when people smoke (behavior), and they know that smoking causes cancer (cognition).

Commitment

A behavioral economics principle that describes the tendency to be consistent with what we have already done or said we will do in the past, particularly if this is public.

For example, researchers asked people if they would volunteer to help with the American Cancer Society. Of those who received a cold call, 4% agreed. A second group was called a few days prior and asked if they would hypothetically volunteer. When the actual request came later, 31% of them agreed.

Confirmation Bias

The tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one’s preexisting beliefs, leading to statistical errors. When people would like a certain idea to be true, they end up believing it to be true. They are motivated by wishful thinking.

For example, a person with low self-esteem is highly sensitive to being ignored by other people, and they constantly monitor for signs that people might not like them.

Decision Fatigue

A lower quality of decisions made after a long session of decision-making.

Repetitive decision-making tasks drain people’s mental resources. Therefore, they tend to take the easiest choice – keeping the status quo.

For example, behavioral economics researchers studied parole decisions made by experienced judges and revealed that the chances of a prisoner being granted parole depended on the time of day that judges heard the case. 65% of cases were granted parole in the morning and fell dramatically (sometimes to zero) within each decision session over the next few hours. The rate returned to 65% after a lunch break and fell again.

Decoy Effect

People will tend to have a specific change in preferences between two options when also presented a third option that is asymmetrically dominated. This well-known principle in behavioral economics can be summarized simply: when there are only two options, people will tend to make decisions according to their personal preferences. But when they are offered another strategically decoy option, they will be more likely to choose the more expensive of the two original options.

For example, when consumers were offered a small bucket of popcorn for $3 or a large one for $7, most of them chose to buy the small bucket, due to their personal needs at that time. But when another decoy option was added – a medium bucket for $6.5, most consumers chose the large bucket.

Dunning-Kruger Effect

A cognitive bias in behavioral economics in which people who are ignorant or unskilled in a given domain tend to believe they are much more competent than they are. In simple words, ‘people who are too stupid to know how stupid they are.’

For example, a nationwide survey found that 21% of Americans believe that it’s ‘very likely’ that they’ll become millionaires within the next 10 years.

Time Discounting / Present Bias

The tendency of people to want things now rather than later, as the desired result in the future is perceived as less valuable than one in the present. When offered a choice of $100 today (SSR – smaller sooner reward) and $100 in one month, people will most likely choose the $100 now. However, if offered a choice of $100 today (SSR) and $1000 in one month (LLR – larger later reward), people will most likely choose the $1000. The challenge is to find the point where people value the SSR and the LLR as being equivalent.

For example, the research found that a $68 payment right now is just as attractive as a $100 payment in 12 months.

Diversification Bias

People seek more variety when they choose multiple items for future consumption than when they make choices sequentially on an ‘in the moment’ basis. For example, before people are going on vacation, they add classical, rock, and pop music to their playlist but eventually end up listening to their favorite rock music.

Ego Depletion

A behavioral economics bias illustrates the concept that people have limited willpower, and it weakens with overuse. Think of willpower as a mental muscle that can get tired.

For instance, studies have shown that when people resist the temptation of chocolates, they have more difficulty with challenging puzzles later. Similarly, when they speak about beliefs they disagree with, their ability to solve tough puzzles also decreases.

Elimination-By-Aspects

A decision-making technique in behavioral economics. When people are faced with multiple options, they first identify a single feature that is most important to them. When an item fails to meet the criteria they have established, they cross the item off their list of options. Different features are applied until a single ‘best’ option is left.

For example, a consumer may first compare cars based on safety, then gas mileage, price, style, etc., until only one option remains.

Hot-Cold Empathy Gap

We have trouble imagining how we would feel in other people’s shoes. We are also not good at imagining how other people would respond to things because we assume they would respond in the same way we would.

For example, people post videos of their kids or bragging about their latest business success on Facebook, assuming that their friends would appreciate it and be happy for them. Unfortunately, this often provokes negative feelings and makes their Facebook friends resentful, angry, or sad.

Endowment Effect

Once people own something (or have a feeling of ownership), they irrationally overvalue it, regardless of its objective value. People feel the pain of loss twice as strongly as they feel pleasure at an equal gain, and they fall in love with what they already have and are prepared to pay more to retain it.

For example, behavioral economics scientists randomly divided participants into buyers and sellers and gave the sellers coffee mugs as gifts. Then they asked the sellers how much they would sell the mug for and asked the buyers how much they would buy it for. Results showed that the sellers placed a significantly higher value on the mugs than the buyers did.

Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

An anxious feeling that can happen when you fear that other people might be having rewarding experiences that you’re missing. Many people have been preoccupied with the idea that someone, somewhere, is having a better time, making more money, and leading a more exciting life.

According to science, FOMO is associated with lower mood, lower life satisfaction, and an increasing need to check social media.

Framing Effect

A cognitive bias in behavioral economics in which people react to a particular choice in different ways depending on how it is presented, as a loss or as a gain. People tend to avoid risk when a positive frame is presented but seek risks when a negative frame is presented.

For example, people are more likely to enjoy meat labeled 75% lean meat as opposed to 25% fat, or use condoms advertised as being 95% effective as opposed to having a 5% risk of failure.

Gambler’s Fallacy (Monte Carlo Fallacy)

The mistaken belief that if something happens more frequently than normal during a certain period, it will happen less frequently in the future, or that if something happens less frequently than normal during a certain period, it will happen more frequently in the future.

For example, if you are playing roulette and the last four spins of the wheel have led to the ball’s landing on black, you may think that the next ball is more likely than otherwise to land on red. In 1913 at the Monte Carlo Casino, the ball fell on the black of the roulette wheel 26 times in a row, and gamblers lost millions betting against the black, thinking mistakenly that the next ball is more likely to land on red, when in fact the odds are the same as they always were – 50:50.

Habit

A routine or behavior that is repeated and tends to occur subconsciously.

A routine or behavior that is repeated and tends to occur subconsciously. Habits are performed automatically because they have been performed frequently in the past. Changing a habit is a process, not an event.

According to science, it takes 66 days to form or change a new habit (and not 21 days like the old myth).

Halo Effect

A behavioral economics bias in which our overall impression of a person influences how we feel and think about his or her character. We assume that because people are good at doing A, they will be good at doing B and C too. Your overall impression of a person (“She is nice!”) impacts your evaluation of that person’s specific traits (“She is also smart!”).

Scientists also found that people tend to rate attractive individuals more favorably for their personality traits or characteristics than those who are less attractive.

Hedonic Adaptation

People quickly return to their original level of happiness, despite major positive or negative events or life changes. When good things happen, we feel positive emotions, but they don’t usually last. The excitement of purchasing a new car or getting a promotion at work is temporary.

One behavioral economics study showed that despite initial euphoria, lottery winners were no happier than non-winners eighteen months later.

Herd Behavior

The tendency for individuals to mimic the actions (rational or irrational) of a larger group. Individually, however, most people would not necessarily make the same choice.

For example, in the late 1990s, investors were investing huge amounts of money into Internet-related companies, even though most of them did not have structured business models. Their driving force was the reassurance they got from seeing so many others do the same.

Hindsight Bias (Knew-It-All-Along Effect)

The tendency of people to overestimate their ability to have predicted an outcome that could not possibly have been predicted. A behavioral economics psychological phenomenon in which people believe that an event was more predictable than it actually was and can result in an oversimplification in cause and effect.

For example, after the Great Recession of 2007, many analysts explained that all the signs of the financial bubble were there. If the signs had been that obvious, how come almost no one saw it coming in real-time?

IKEA Effect

A behavioral economics bias in which people place a disproportionately high value on products they partially created.

For example, in one study, participants who built a simple IKEA storage box themselves were willing to pay much more for the box than a group of participants who merely inspected a fully built box.

Less-Is-Better Effect

When low-value options are valued more highly than high-value options. This effect occurs only when the options are evaluated separately. This way, the evaluations of objects are influenced by attributes that are easy to evaluate rather than those that are important.

For example, research revealed that:

- A person giving an expensive $45 scarf as a gift was perceived to be more generous than one giving a $55 cheap coat.

- An overfilled ice cream serving in a small cup with 7 oz of ice cream was valued more than an underfilled serving in a large cup with 8 oz of ice cream.

Licensing Effect

When people allow themselves to indulge after doing something positive first. Drinking a diet coke with a cheeseburger can lead one to subconsciously discount the negative attributes of the meal’s high caloric and cholesterol content. Going to the gym can lead us to ride the elevator to the second floor.

A behavioral ecsonomics study showed that people who took multivitamin pills were more prone to subsequently engage in unhealthy activities.

Loss Aversion

People tend to prioritize avoiding losses over acquiring equivalent gains, a fundamental principle in behavioral economics. It’s better not to lose $5 than to find $5. The pain of losing is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining.

For example, scientists randomly divided participants into buyers and sellers and gave the sellers coffee mugs as a gift. They then asked the sellers for how much they would sell the mug and asked the buyers for how much they would buy it. Results showed that the sellers placed a significantly higher value on the mugs than the buyers did. Loss aversion was the cause of that contradiction.

Mental Accounting

A behavioral economics bias that describes the tendency of people to divide their money into separate accounts based on subjective criteria, like the source of the money and the intent for each account.

For example, people often have a special fund set aside for a vacation, while carrying substantial credit card debt, even though diverting funds from debt repayment increases interest payments and reduces net worth.

Similarly, another study revealed that supermarket shoppers spent less money paying with cash than with credit cards. Comparing the price of goods to a smaller mental account (cash) than to a larger mental account (credit card) increased the pain of payment.

Naive Diversification

When people have to make several choices at once, they tend to diversify more than when making the same type of decision sequentially.

For example, when people are asked to choose now which of six snacks to consume in the next three weeks, they pick more kinds of snacks than when they are asked to choose once a week from six snacks to consume that week for three weeks. As a result, investors tend to think that by simply investing in a number of unrelated assets, a portfolio will acquire enough diversification to enjoy relative freedom from high risk and potential for profit.

Optimism Bias

A behavioral economics bias that causes people to believe that they are at a lesser risk of experiencing a negative event compared to others. When it comes to predicting what will happen to us tomorrow, next week, or fifty years from now, we overestimate the likelihood of positive events.

For example, smokers tend to feel they are less likely than other individuals who smoke to be afflicted with lung cancer. Similarly, motorists tend to feel they are less likely to be involved in a car accident than the average driver. Research has also found that people show less optimistic bias when experiencing a negative mood, and vice versa.

Overconfidence Effect

We systematically overestimate our knowledge and our ability to predict. Overconfidence measures the difference between what people really know and what they think they know. It turns out that experts suffer even more from the overconfidence effect than laypeople do.

Behavioral economics studies have found that over 90% of US drivers rate themselves above average, 68% of professors consider themselves in the top 25 percent for teaching ability, and 84% of Frenchmen believe they are above-average lovers.

Overjustification Effect

The loss of motivation and interest as a result of receiving an excessive external reward (such as money and prizes). When being rewarded for doing something actually diminishes intrinsic motivation to perform that action.

For example, researchers rewarded children for doing activities they already enjoyed, like solving puzzles. Then, the children were allowed to engage in these same activities on their own, when no rewards would be forthcoming. The results: children engaged in these activities less often than they did before.

Pain of paying

A behavioral economics rule that explains that some purchases are more painful than others, and people try to avoid those types of purchases. Even if the actual cost is the same, there is a difference in the pain of paying, depending on the mode of payment. Purchases are not just affected by the price, utility, and opportunity cost, but by the pain of paying attached to the transactions. Studies show that people feel the pain of paying the most when they:

- Paying in cash (as opposed to credit card).

- Paying a separate fee/commission (as opposed to a fee included in the total purchase price).

- Paying as they consume (as opposed to one-time payment).

- Paying frequently (as opposed to prepaid).

- Paying on their own (as opposed to receiving a gift from their partners).

Partitioning

When the rate of consumption decreased by physically partitioning resources into smaller units.

For example, cookies wrapped individually, a household budget divided into categories (e.g., rent, food, utilities, transportation, etc.). When a resource is divided into smaller units, consumers encounter additional decision points – a psychological hurdle encouraging them to stop and think.

Peak-End Rule

People judge an experience largely based on how they felt at its peak (the most intense point) and its end, rather than on the total sum or average of every moment of the experience. This behavioral economics effect occurs regardless of whether the experience is pleasant or unpleasant and how long the experience lasted.

In a research, participants engaged in two experiences: short and long trials. In the short trial, they soaked their hands in water at 14°C for 60 seconds. In the long trial, the same participants soaked their hands in water at 14°C for 60 seconds and kept their hands under the water for an extra 30 seconds at 15°C. When the researchers asked the participants to choose which trial to repeat, the majority chose the long trial.

Similarly, a study showed that in uncomfortable colonoscopy procedures, patients evaluated the discomfort of the experience based on the pain at the worst peak and the final ending moments. This occurred regardless of the procedure length or the pain intensity.

Priming

When people are exposed to one stimulus, it affects how they respond to another stimulus. Their unconscious brain is affected by a stimulus like colors, words, or smells, which creates an emotion that will affect their next actions.

For example, one behavioral economics study revealed that when restaurants played French music, diners ordered more wine. In a different study, when websites’ visitors were exposed to a green background with pennies on it, they looked at the price information longer than other visitors.

Procrastination

The avoidance of doing a task that needs to be accomplished. It is the practice of doing more pleasurable things in place of less pleasurable ones or carrying out less urgent tasks instead of more urgent ones.

It is estimated that 90% of college students engage in procrastination, and 75% consider themselves procrastinators.

Projection Bias

The tendency of people to overestimate the degree to which other people agree with them. People tend to assume that others think, feel, believe, and behave much like they do.

This behavioral economics bias also influences people’s assumptions about their future selves. They tend to believe that they will think, feel, and act the same in the future as they do now. For this reason, we sometimes make decisions that satisfy current desires, instead of pursuing things that will serve our long-term goals.

For example, if people go to the supermarket when they are hungry – they tend to buy things they don’t normally eat and spend more money as a result. This happens because, at the time of shopping, they unconsciously anticipate that their future hunger will be as great as it is now.

Ratio bias

People’s difficulties in dealing with proportions or ratios as opposed to absolute numbers.

In a study, participants rated cancer as riskier when it was described as killing 1,286 out of 10,000 people than as killing 24.14 out of 100 people. The fact that 12.86% could be considered riskier than 24.14% is a clear demonstration that the ratio bias can strongly influence the perception of risk.

In a similar behavioral economics study, participants rated the statement “36,500 people die from cancer every year” as riskier than the statement “100 people die from cancer every day.

Reciprocity

A simple behavioral economics principle – If someone does something for you, you’ll naturally want to do something for them. When you offer something for free, people feel a sense of indebtedness towards you.

For example, researchers tested how reciprocity can increase restaurant tipping. Tips went up by 3% when diners were given an after-dinner mint. Tips went up to 20% if, while delivering the mint, the waiter paused, looked the customers in the eye, and then gave them a second mint while telling them the mint was especially for them.

In another study, 11% of people were willing to donate an amount worth one day’s salary when they were given a small gift of candy while being asked for a donation, compared to 5% of those who were just asked for the donation.

Regret aversion

People anticipate regret if they make a wrong choice and take this anticipation into consideration when making new decisions. Fear of regret can play a large role in dissuading or motivating someone to do something.

For example, an investor decides to buy a stock based on a friend’s recommendation. After a while, the stock falls by 50%, and the investor sells the stock at a loss. To avoid this regret in the future, the investor will research any stocks that his friend recommends. On the other hand, if the investor didn’t take his friend’s recommendation and the price increased by 50%, next time, the investor would be less risk-averse and would buy any stocks his friend recommends.

Representativeness heuristic

People tend to judge the probability of an event by finding a ‘comparable known’ event and assuming that the probabilities will be similar. When people rely on representativeness to make judgments, they are likely to judge wrongly because the fact that something is more representative does not actually make it more likely.

For example, in a series of 10 coin tosses, most people judge the series HTHTTTHHTH to be more likely than the series HHHHHHHHHH. In business, if a customer meets a salesman from a certain company that is aggressive, the customer might assume that the company has an aggressive culture.

In behavioral finance, investors might prefer to buy a stock based on the company’s positive characteristics (e.g., high-quality products) as an indicator of a good investment.

Scarcity

The more difficult it is to acquire an item, the more value that item has. When there is only a limited number of items available, the rarer the opportunity, the more valuable it is. People assume that things that are difficult to obtain are usually better than those that are easily available. They link availability to quality. On “Black Friday,” more than getting a bargain on a hot item, shoppers thrive on the competition itself, in obtaining the scarce product.

In a famous behavioral economics study, one group of participants was given a jar with ten cookies, a second group was given two cookies, and a third group was initially given ten cookies, which were then reduced to two cookies. When asked, the participants from the third group rated their cookies the highest.

Social Proof

A psychological phenomenon in behavioral economics where people reference the behavior of others to guide their own behavior.

Studies show that over 70% of Americans say they look at product reviews before making a purchase, and 83% of consumers say they trust recommendations over any other form of advertising.

There are five types of social proof for your product or service:

- Experts’ social proof – an approval from credible industry leaders. If people buy something that they’re unfamiliar with, they tend to rely on expert’s opinion.

- Experts’ social proof – an approval from credible industry leaders. If people buy something that they’re unfamiliar with, they tend to rely on expert’s opinion.

- User social proof – an approval from current customers/users of a product or service. This includes customer testimonials, case studies, and product/service reviews.

- Wisdom of the crowd – an approval from a large group of people. When lots of people are using or buying a product, others want to follow.

- Wisdom of friends – an approval from friends and people you know. 92% of consumers trust recommendations from people they know and pay 2X more attention to recommendations from friends.

Sunk Cost Fallacy

The tendency of people to irrationally follow through on an activity that is not meeting their expectations because of the time and/or money they have already spent on it.

The logic form: X has already been invested in project Y. Z more investment would be needed to complete project Y, otherwise, X will be lost. Therefore, Z is justified.

This behavioral economics principle explains why people finish movies they aren’t enjoying, finish meals in restaurants even though they are full, hold on to underperforming investments, and keep clothes in their closet that they’ve never worn.

Zero Price Effect

When any item priced at exactly zero will not only be perceived to have a lower cost but will also be attributed greater perceived value. When people are offered something for free, they have an extremely positive reaction that clouds their judgment.

In an experiment, one group of participants were given three choices: Buy a “low-value product” (a Hershey’s Kiss) for one cent, buy a “high-value product” (a Lindt truffle) for 14 cents, or buy nothing. The second group faced a slightly different choice, in which the cost of each chocolate was lowered by a single cent. The Lindt truffle was now 13 cents, while the Hershey’s Kiss was free. The results showed that when both chocolates are not free, the majority preferred the higher value product. But when the lower value product was offered for free, the majority of people preferred it.

Examples of Behavioral Economics

In this section, I explore real-life examples of how companies use behavioral economics to reshape their consumer engagement and drive business success. These illustrations demonstrate how they create persuasive customer experiences, leading to increased conversions, trust, and competitive advantage.

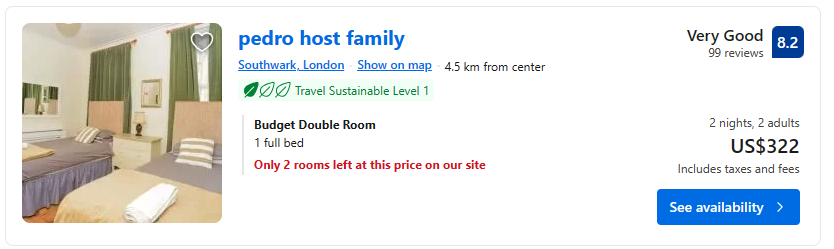

Example 1: Scarcity & Fomo – “Only 2 Rooms Left”

Booking.com effectively employs the behavioral economics principle of “scarcity” to influence consumer behavior through a simple yet persuasive tactic – indicating “only 2 rooms left” in their hotel advertisements. This technique capitalizes on people’s natural aversion to missing out on opportunities, known as the fear of missing out (FOMO).

By suggesting a limited quantity of rooms, Booking.com creates a sense of urgency and scarcity that prompts potential guests to act quickly. Consumers may be more inclined to make a reservation upon seeing this message, fearing that they might lose the chance to secure a room if they delay. This leverages the psychological bias towards valuing things that appear rare or in high demand, aligning with the core principle of scarcity in behavioral economics to drive conversions and bookings on their platform.

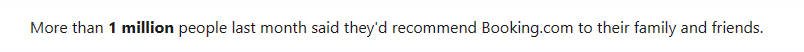

Example 2: Social Proof – “1M People Recommended”

Skillfully utilizing the principle of “social proof,” Booking.com enhances its checkout page with the compelling statement, “More than 1 million people last month said they’d recommend Booking.com to their family and friends.”

This artful application of behavioral economics capitalizes on our inherent inclination to seek guidance and assurance from the choices and judgments of our peers. By underscoring the substantial number of individuals who have endorsed their platform, Booking.com imparts a profound sense of security and trust to potential customers. The message suggests that a substantial community of users has already made the same decision and found it to be a commendable one, gently encouraging prospective clients to do likewise.

This element of social proof not only reinforces confidence during the booking process but also operates as a persuasive nudge, significantly increasing the likelihood of users finalizing their reservations and, in doing so, bolsters Booking.com’s preeminence in the fiercely competitive online travel sector.

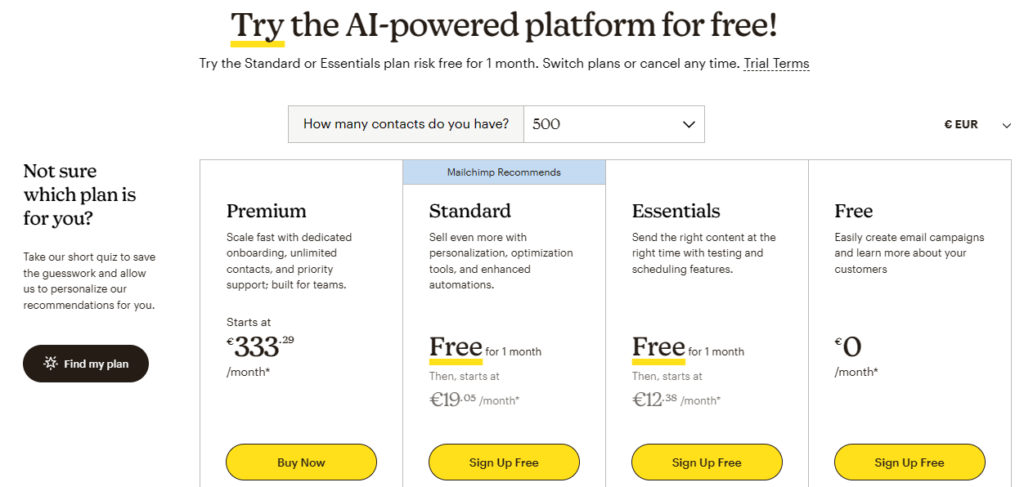

Example 3: Anchoring – SaaS Pricing

Mailchimp effectively implements the behavioral economics concept of “anchoring” on their SaaS pricing page. When displaying their subscription plans, Mailchimp arranges them in a sequence that starts with the most expensive plan followed by the less costly ones. This deliberate arrangement leverages the psychology of pricing perception: the high-priced first plan serves as an anchor, influencing the way potential customers assess the value of the subsequent options.

By establishing a relatively costly starting point, Mailchimp creates a reference for comparison, leading the other plans to seem more affordable in contrast. This strategic use of anchoring subtly nudges customers toward considering the lower-priced options as better deals, thereby increasing the likelihood of users opting for these plans and improving Mailchimp’s conversion rates.

Behavioral Economics Applications

Let’s delve into the practical applications of behavioral economics across four pivotal areas: Pricing Strategy, Product Management, Marketing, and Sales. Companies leverage these insights to enhance understanding of consumer behavior, drive profitability, and create more emotionally resonant products and marketing campaigns.

Pricing Strategy

The implementation of behavioral economics in pricing strategy has revolutionized the way businesses set and adjust their prices. By leveraging insights from behavioral economics, companies can better understand how consumers make purchasing decisions.

For instance, the use of price anchoring, where a higher initial price is presented to make a subsequent, lower price seem more attractive, can exploit consumers’ irrational tendencies. Additionally, the framing of prices and discounts in a way that aligns with consumers’ mental shortcuts and biases can influence their willingness to buy. This approach not only maximizes profitability but also enhances customer satisfaction by making prices more transparent and fair.

In essence, incorporating behavioral economics into pricing strategies enables businesses to create pricing models that are not only economically rational but also psychologically appealing, ultimately optimizing their competitiveness and success in the market.

Product Management

Incorporating insights from behavioral economics into product management practices has redefined the way products are conceptualized, developed, and delivered. By drawing upon the principles of human behavior and decision-making, product managers can gain a deeper understanding of their target audience’s motivations and preferences. This knowledge becomes a cornerstone for crafting products that are not only functional but also emotionally resonant and user-driven. Strategies such as user-centered design, behavioral nudges, and personalized experiences are now integral to product management, enabling companies to create solutions that better align with the intricacies of human psychology.

Ultimately, behavioral economics in product management is an invaluable tool in the quest to meet user needs, encourage engagement, and drive innovation in a rapidly evolving marketplace.

Marketing

The infusion of behavioral economics into marketing has led to a profound transformation in the way businesses engage with their target audiences. By tapping into the intricate landscape of human decision-making, marketers can design campaigns that resonate with consumers’ cognitive biases and emotional inclinations. Concepts like loss aversion and decision fatigue guide marketers in framing promotions and offers to capture attention and influence choices. Furthermore, the use of emotional storytelling and neuro-marketing principles empowers businesses to forge deeper, more authentic connections with customers.

In a rapidly changing marketplace, the application of behavioral economics in marketing not only enhances the impact of campaigns but also fosters brand loyalty and customer advocacy by aligning marketing strategies with the quirks and complexities of human behavior.

Sales

The application of behavioral economics in sales tactics has given rise to a new era of customer-focused approaches, where understanding and influencing decision-making play pivotal roles in closing deals. By delving into the intricacies of human decision-making, sales professionals can harness a deeper understanding of their customers’ motivations and cognitive biases. This knowledge becomes a powerful tool for tailoring sales strategies and communication to resonate with customers on a psychological level.

Salespersons can leverage behavioral insights to craft compelling narratives, employ persuasive language, and structure deals in a way that aligns with consumers’ emotional triggers and mental shortcuts. Techniques such as reciprocity, social proof, and framing can be skillfully integrated into the sales process, creating a more compelling and memorable customer experience.

In this dynamic landscape, the synergy between behavioral economics and sales not only optimizes conversion rates but also fosters stronger client relationships and positions businesses for long-term success.

Best Behavioral Economics Books

Exploring the fascinating world of behavioral economics, I’ve compiled a list of the three most important books that help us understand how humans make decisions. These books offer valuable insights into the blend of psychology and economics, making them a must-read for anyone curious about the science of choice.

1. Thinking Fast and Slow

A groundbreaking book “Thinking Fast and Slow” by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman that delves into the intricacies of human thought processes, offering profound insights into the realm of behavioral economics. In this captivating exploration, Kahneman introduces readers to the two systems that drive our thinking:

- System 1 – the fast and instinctual mind that relies on intuition and emotions.

- System 2 – the slower, more deliberate mind that engages in logical reasoning and critical thinking.

The book masterfully unravels the various cognitive biases and heuristics that impact our daily decision-making, revealing how our minds often operate on autopilot, leading to irrational judgments and choices. Through vivid anecdotes and thought-provoking examples, Kahneman provides a comprehensive look at how these systems interact and influence our lives, shedding light on the psychology behind human decision-making and offering invaluable insights for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of their thought processes in the context of behavioral economics. “Thinking, Fast and Slow” is a must-read for those eager to explore the hidden dynamics of their own minds and the mysteries of human behavior in the context of behavioral economics.

2. Nudge

“Nudge,” co-authored by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein, is an innovative work that combines the frontiers of behavioral economics and public policy to offer a fresh perspective on how individuals make choices and decisions. This insightful book delves into the concept of choice architecture, where minor, subtle alterations in the way choices are presented can significantly impact people’s decisions.

Leveraging the principles of behavioral economics, Thaler and Sunstein propose that governments and institutions can ‘nudge’ individuals toward making better choices for themselves and society. They discuss various practical examples where nudges have been applied successfully, from promoting healthier eating habits to enhancing retirement savings.

“Nudge” presents a compelling case for how behavioral insights can be used to shape policies and design environments that foster better decision-making, ultimately highlighting the profound influence of behavioral economics on our daily lives and the policymaking process.

3. Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions

In “Predictably Irrational” by Dan Ariely, the fascinating intersections of human behavior and economic decision-making are meticulously explored within the domain of behavioral economics. Ariely delves into the irrational tendencies that underlie our choices, revealing a captivating array of cognitive biases and quirks that influence our everyday lives.

Through a series of captivating experiments and real-world examples, the book offers a profound analysis of why people act in predictably irrational ways when faced with economic decisions. Ariely’s engaging narrative not only unravels the mysteries of our often-confounding choices but also provides valuable insights into how behavioral economics can be harnessed to navigate the intricate landscape of decision-making.

Final Thoughts

In summary, behavioral economics provide invaluable insights into the fascinating realm of human decision-making. These mental shortcuts influence how we perceive the world, make choices, and interact with others. Whether it’s the Affect Heuristic shaping our emotional responses, the Anchoring bias affecting how we make financial decisions, or the Power of Defaults guiding our choices, behavioral economics biases play a pervasive role in our lives.

By understanding these behavioral economics principles and the impact they have on our behavior, individuals, businesses, and policymakers can make more informed decisions. Recognizing the role of biases in areas like marketing, finance, and social interactions empowers us to navigate these complexities more effectively.

The groundbreaking work of Daniel Kahneman, which led to a Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, underscored the significance of behavioral economics biases in shaping our world. This comprehensive list of biases, presented in accessible language with real-world examples, serves as a valuable resource for those seeking a deeper understanding of behavioral economics.

As you explore the myriad ways behavioral economics influence our thinking and actions, remember that knowledge is power. Armed with this understanding, you can design better products, craft more effective marketing strategies, and ultimately make more rational decisions in an often-irrational world.

Pingback: Pricing Strategy - The Complete Guide & Examples For 2024

Pingback: Digital Marketing Strategy - The Complete Guide For 2024